The capacity to translate music notes and rhythms into visual forms, generally called Visual Music is one of the crossbreed art concepts that I feel more identified with. Also because it connects two of my biggest passions: Visuals (all kind of graphic expression) and music. Therefor it was a matter of time to write a piece about all this in my blog. Indeed AV Brain Feeder is meant not only for sharing music and videos, but also to spread ideas and concepts connected to my work, in order to explain somehow the insides of what a visual artist is.

To See Music

I must confess that the writing of this piece is motivated by the Doodle that Google published last week to celebrate Oskar Fischinger’s 117th Birthday. Since the creation of this blog I had in mind to publish a post about Visual Music and other related to subjects, but time passed by quickly. Anyway, it’s never too late, even more seeing the great attention that this Doodle caught.

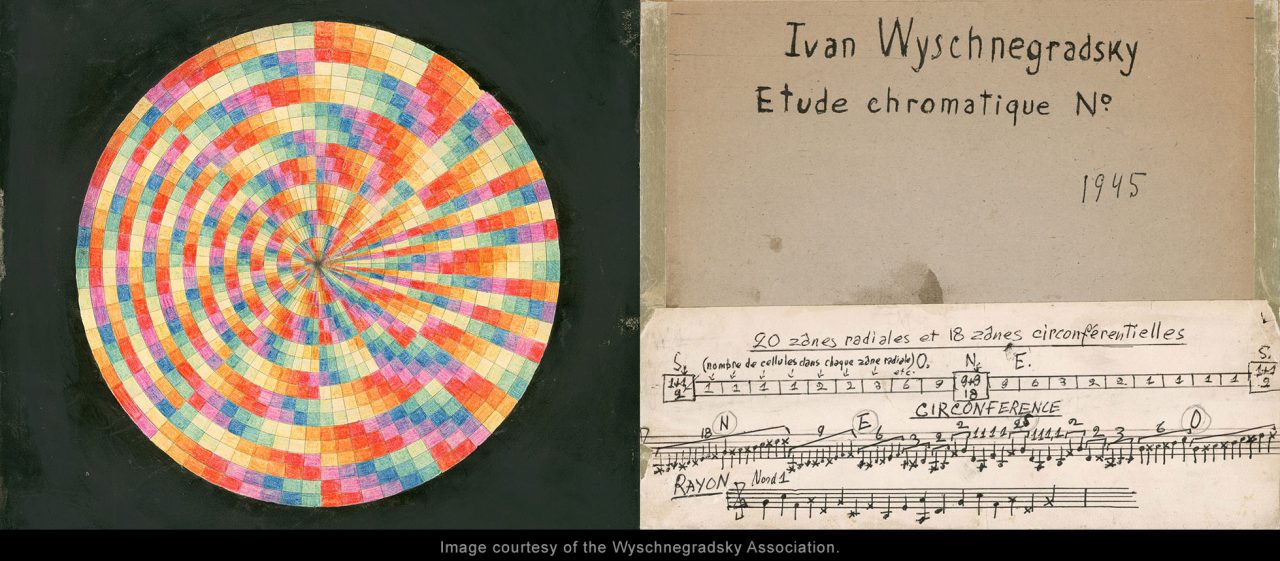

I believe that Doodle amazed all kinds of viewers by the fact of being able to create melodies (and visuals) by switching on and off digital light buttons, in the style of what a usual pad midi controller does, like a Novation Launchpad Pro or an Ableton Push Controller, to name just two popular examples in music tools. But the concept of Visual Music and the work of Oskar Fischinger is something else. It’s not my purpose to write a biography or compile the history related to music visualization. But if you are interested I recommend you to dig also in the works of Wassily Kandinsky, Ivan Wyschnegradsky (the image above), the avantgarde Clavilux from Thomas Wilfred (the top image on the header), the pioneering experiments from Mary Ellen Bute, and many others such as Norman McLaren, Barry Spinello, Steven Woloshen and Richard Reeves to get an idea of the origin of this discipline.

Personally, I’m more interested in the present time (without forgetting the past) and the contemporary artists that somehow represent and push the boundaries of music visualization nowadays. About this very same subject I curated a video program last year for the Spanish José Guerrero Art Center in Granada. Under the title Sonidos Ilustrados (Illustrated sounds) I compiled works from visual artists and musicians such as Max Hattler, Brandon Blommaert, Lasal, Paul Prudence, Natalia Stuyk, Felix Faire, Jonathan Gillie and Boris Divider among others. Videos that you can enjoy in this link.

What Do You See?

The concept of “seeing” sounds is undoubtedly connected with the neurological phenomenon of synesthesia, in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. The most common synesthesia phenomenon is the one connecting hearing and seeing. In my opinion we all have a certain degree of that, from those who doesn’t connect at all two senses to others who experience this in a massive scale, becoming a problem for interaction between the individual and his/her environment.

Also people experimenting with psychedelic drugs often find themselves cross-wiring different senses. In this sense, I believe a synesthetic perception can be trained, not only with drugs but also exercising regularly your mind (closing your eyes and focussing in imagine the music you are listening to).

But it’s not just a human perception or invention. The connection between color and sound patterns are part of nature. It’s highly interesting to dive in color theories, sound physics and the correlation between sound, color and frequency. There is a lot of studies and videos published on internet about this singular connection.

So, how can you visually translate a piece of music? When we talk about instrumental music (no matter the style, just music without lyrics) the closer visual interpretation is an abstract composition based on color, shapes, brightness and size. But when music contains lyrics, then there is another art form involved: poetry or story telling, words can define so much the way a human being expresses an idea that are capable of creating a concrete image in the mind of the listener, in that case the visual interpretation of a song could be a more narrative and realistic view. Of course, instrumental music can be also narrative, cinematic, and maybe the view of a landscape, for example, could reflect that music just perfectly. At the end we connect feelings with music, so whatever image could bring us back that feeling would work. This Visual Music concept not only applies to live music performances, it also works for music videos somehow.

Visual Music Now!

If I write this article, and I hope you got here, is because I think Visual Music is nowadays a pretty contemporary discipline, and each day it gets bigger and more present in the music scene. The first indication of this is that every day is more common to see AV live shows announced in festivals or as tours, usually teaming up musicians and visual artists. And in some really rare cases the same artist is the author of both, meaning: music and visuals, both! equally well produced and performed.

One of the reasons why Visual Music is coming back strong from the past is the development in the past decade of visual softwares capable to analyze sound and be programmed to react to it. Leaving aside raw coding, analog video mixers and other light techniques, the most popular softwares for such are VDMX, Resolume and Modul8, which are commonly VJing softwares. So, Visual Music and VJing are the same? No… And yes. But that’s a question I prefer to go deeper in another post. The same goes for softwares… I should mention that there is more options such VVVV, Isadora, the upcoming Laserjuice XYZ (to control lasers), as well as analog video synths, video racks and their correspondent digital simulators.

Somehow the same way electronic music keeps on expanding both in digital and analog madness, the visual field is also bursting with new softwares and a strong revival and experimentation with old ways of mixing and editing video live. But this is not the only similarity between music and visuals. Also the creative process and tools are so similar that each day the correlation between both is easier and at the same time more complex, probably a dream made true for pioneers such Fischinger, Bute and Wilfred.